“When a broken arm heals inside the sleeve, the bones misalign and cause lifelong pain and restricted movement.”

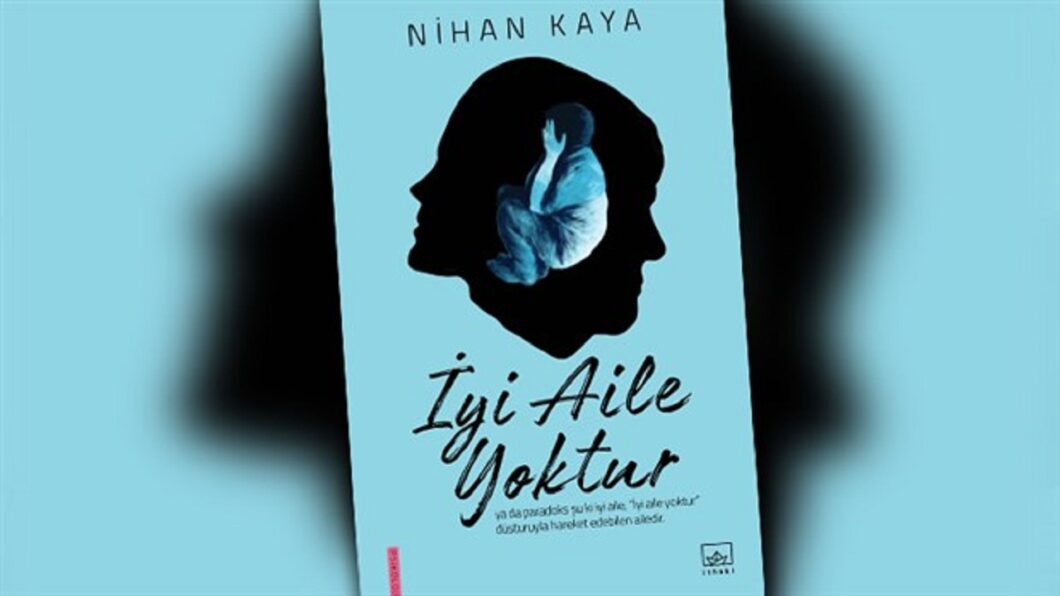

This book is quite difficult to promote. That’s why, all I want to say is “Read it, you will understand what I mean.”

Firstly, the book brings down everything considered “sacred,” starting with the mother, parents, school, teachers, society, state, beliefs (religious or ideological), and continues by examining them on Earth. Everything is open for questioning. As you read, you start to realize how these sacred values serve the system’s continuity. These questions can begin with ourselves, if we are lucky. I say “if we are lucky,” because since the very first years of childhood, our inner voice has been silenced. If we have betrayed ourselves to win the “love” of our parents, how can we hear that inner voice? If we mistake the voice of authority (parents, society, etc.) for our own, how can we engage in self-examination? How can a parent who cannot hear their own child’s voice hear the child’s voice?

The author says that, as a result, the child learns to obey by betraying themselves, by respecting adults. “Obedience is the child’s betrayal of themselves,” and “A person who betrays themselves can easily betray others,” the author continues. The book cites many important figures from the field of trauma and delves into not so obvious but deeply ingrained cultural traumas that shape an individual’s personality. It raises awareness by discussing the formation processes of these traumas that may go unnoticed. “Culture is the family of the family,” the author states. When there is a hierarchy, real respect cannot exist. At home, the child’s position as “the other” is painfully apparent.

Through these subtle and visible traumas, the book explains the psychodynamics with the help of citations and everyday life examples, making it easy for the reader to understand. The reader inevitably starts looking inward.

A metaphor, for example: the saying “An arm breaks but stays inside the sleeve” symbolizes how an individual is subdued right from the start, preventing them from facing the necessary confrontation with themselves for healing. “When a broken arm heals inside the sleeve, the bones misalign and cause lifelong pain and restricted movement.” Isn’t that striking?

The author also touches upon the societal gender roles imposed on men and women, and the children and adults crushed beneath them. But the focus is mainly on children because, after all, children didn’t ask to be born. The author sharply criticizes the “unforgiving” nature of this burden placed on them by adults. The author discusses how the suffering woman, unable to fulfill her role, transmits this trauma to her daughters, perpetuating it in an unhealthy manner.

The book consists of four sections.

The first chapter is titled “Childhood is Hell,” and the book opens with this line. It continues with a quote from Hallac-ı Mansur: “Hell is not the place where we suffer, it’s the place where no one sees our suffering.”

From the moment a child is born, they need unconditional love and acceptance, as essential as air and water. The author stresses that parents should not raise their children according to their own needs and whims but rather according to the child’s needs. The importance of recognizing the child as an individual from birth is emphasized. The author points out that the phrase “Is that a child in front of you?” is a belittling expression.

“Becoming a mother brings all of one’s traumas, complexes, weaknesses, and past disappointments right into the mirror.” “It’s not the child who is problematic, it’s the parents who are,” says the author. The parent is not the one who unconditionally loves, forgives, and has infinite tolerance—the child is.

In Turkey, the concept of “respect” is emptied of meaning. Respect is used to legitimize disrespect, confused with obedience. Where there is respect, there is no hierarchical relationship. Unfortunately, respect is often least found in environments that lack it. If a cliché is needed, “respect for the child” would be a more accurate cliché than “respect for the elders.”

The book also discusses how forcing patients to forgive their parents in psychotherapy is related to the therapist’s upbringing. It uses quotes from Alice Miller, who the author frequently cites: “Forgiving is covering it up.” In this context, we also see how Freud contributed to this cover-up. According to the author, one does not need to forgive their parents in order to become a mature individual. “The one who suffers is the one who is expected to sacrifice even after the harm.”

The second section of the book is “The History of Modern Education.” It explores the history of raising obedient individuals for the system, introduces the Montessori Schools as positive examples, and demonstrates how creative children can be when allowed to express themselves.

The third chapter is titled “Maternity Wards are for the Doctors, Not for the Mothers and Babies.”

The fourth and longest section contains many citations, which may make the reader eager to read the books the author cites. The final chapter is quite lengthy, and like this promotional text, it seems impossible to finish it.

It’s better if I simply list a few of the 31 books and two films cited by the author, based on what I’ve managed to count. I’ve already started reading the author’s “There Is No Perfect Society,” which complements “There is No Perfect Family,” and it’s just as captivating.

- The Body Never Lies, For Your Own Good, Breaking the Silence / Breaking the Wall of Silence, Life Paths, Forbidden Knowledge, There Was Education in the Beginning, The Drama of the Gifted Child, You Won’t Realize It – Alice Miller

- The Courage to Write – Nihan Kaya

- The Killing of a Sacred Deer – FILM – Yorgos Lanthimos

- Women Who Run with the Wolves – Clarissa P. Estes

- Trauma and Recovery – Judith Lewis Herman