Once upon a time, our homes had guest rooms. Rooms whose doors were always closed, sometimes even locked in certain homes. These rooms were meticulously kept clean, and children were never allowed to enter. This forbidden, secret shrine would arouse immense curiosity in children, leading them to secretly peek inside whenever the door was slightly ajar. Then, lavish tables would be set for guests in these rooms, while children were forced to eat in the kitchen at a less elegant, cramped table. This treatment made children feel as if they were invisible in the eyes of adults. Parents, without realizing it, would make their children feel unimportant.

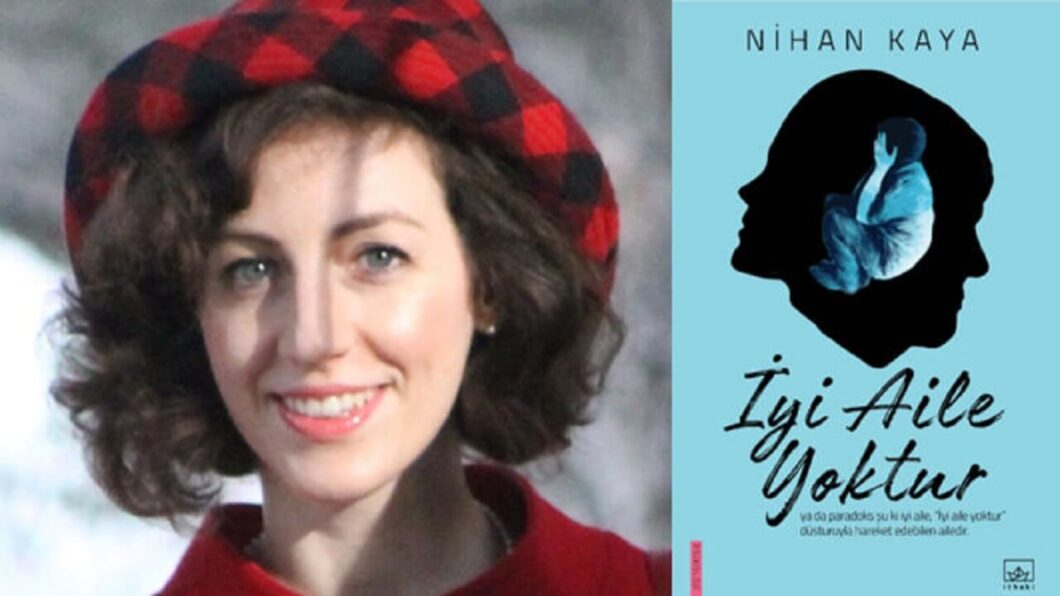

However, as Nihan Kaya states in her book “There Is No Good Family,” “For a child to become a happy adult, there is only one thing we, as parents, can do: ensure that the child feels valued.” In this book, Kaya reveals the drama of childhood and illustrates how parents can turn childhood into a nightmare. She invites parents—who themselves emerged from that nightmare without realizing their own wounds—to heal their own pain and, in turn, rescue their children from the same suffering. “If we can face how wounded our inner child is, we will naturally start treating both our inner child and real children correctly,” says Kaya, as we discuss the drama of childhood.

**Saying “There Is No Good Family”

HAMİDİ:** Most of us, as parents, are unaware of how we harm our children. We believe we are wonderful and flawless parents. The title of your book is an awakening call, urging self-reflection. Why is there “No Good Family”?

KAYA: For centuries, we have said, “There is no good child,” meaning, “No matter what, a child can never repay their parents’ debt.” But we fail to see how destructive this seemingly innocent saying is. A good family is one that can say, “There is no good family.” Every parent inevitably harms their child in some way. In my book, I try to explain why and how being a good parent lies in accepting this unavoidable reality. By “family,” I do not mean just the nuclear family; I refer to all the institutions and rigid traditions that we have institutionalized and sanctified. The institutionalization and sanctification of the family help to conceal the harm done to children, and my goal is to reveal how this happens. Many of the phrases and patterns we have memorized prevent us from seeing how children are truly oppressed.

HAMİDİ: This book essentially unveils the drama of childhood…

KAYA: That is a very accurate way to put it. In a single sentence, yes.

HAMİDİ: At the beginning of your book, you say, “Childhood is a hell.” You quote Hallac-ı Mansur: “Hell is not the place where we suffer. Hell is the place where no one knows that we suffer.” Childhood is exactly like that. By the time a child realizes that the treatment they endured was not “normal,” it is too late—they are already an adult. How can parents recognize this suffering and become aware of it?

KAYA: I address not just parents but everyone, regardless of age. Whether we interact with a real child or the symbolic child within us, the principle remains the same. Each child is unique, and so are the situations they face. Each child experiences pain in their own way, often without even realizing it. The only way to recognize a child’s pain is by truly knowing that child. However, when interacting with children, we are so convinced of our own superiority, expertise, and knowledge that this arrogance prevents us from truly understanding them. When our minds are preoccupied with teaching children, we fail to see who they really are.

The problem with “child education” starts precisely with the word “education.” This also applies to our inner child. Children represent our capacity for renewal, progress, and transformation; they are our potential to become the person we have not yet become. Those who see children as beings that need to be shaped and disciplined also treat their inner child in the same way, which stifles creativity and openness to change. My book focuses on this awareness.

Reaching the Inner Child

HAMİDİ: Our parents—and their parents before them—emerged from the deepest and most painful part of this “hell.” They raise (or perhaps “erase”?) their children with the burdens they carry from their past. Raising awareness among them and helping them recognize their own wounds seems difficult, but is it possible?

KAYA: The key is for these individuals—whether parents, grandparents, aunts, or anyone else—to recognize how wounded their own inner child is. My goal is not to reach the inner parent but the inner child.

Readers of “There Is No Good Family” fall into two categories: those who read it with their inner parent and those who read it with their inner child. Those who approach the book as parents—whether they have children or not—have often internalized the harsh, authoritarian voice of their own parents and do not recognize how this voice continues to suppress their inner child. As a result, despite my book not having an angry tone, they perceive it as harsh because they project their inner parent’s strict voice onto it.

However, my book does not lecture or reprimand parents or anyone else. It solely aims to show why and how children suffer. The issue is not how wounded our inner child is; it is our lack of courage to acknowledge how we continue to wound our inner child with our inner parent. Without confronting this, we cannot progress.

An elderly person with the courage to face themselves can benefit greatly from my book, while an educated young adult who has not yet become a parent might perceive it as harsh and reject it because they are not ready to confront their inner child. This is entirely dependent on one’s capacity for self-reflection.

Saying “But parents…” in defense of our upbringing only serves to justify the harm that was done. The true violence lies in these justifications, not in recognizing and addressing the harm. All evil in the world stems from the taboo surrounding parents.

“There Is No Good Family” contains no angry statements, yet those who resist confronting their inner wounds perceive it as an attack. The difference between those who have confronted their childhood wounds and those who have not determines everything—how we view ourselves, life, and children.

HAMİDİ: You say, “I will not write a novel in a world where children do not experience heartbreak, or where adults recognize the heartbreak of wounded children.” One wants to hold on to hope and keep striving for such a world. But maintaining hope is not always easy. How can we keep this hope alive?

KAYA: In my novel “Kırgınlık,” I described a child who grew up in prison and did not know what the word “curtain” meant. Writing about that child, for me, was hope itself in the midst of despair.

My book is precisely that: an attempt to find hope within hopelessness. Writing it was an act of defiance, a declaration of resilience. As poet Can Yücel once said, “Poetry is born from despair. Only those who are hopeless can write poetry, create art, or build something meaningful.” “There Is No Good Family” and all my other books exist because of that very truth.